Georges Seurat: Anarchist?

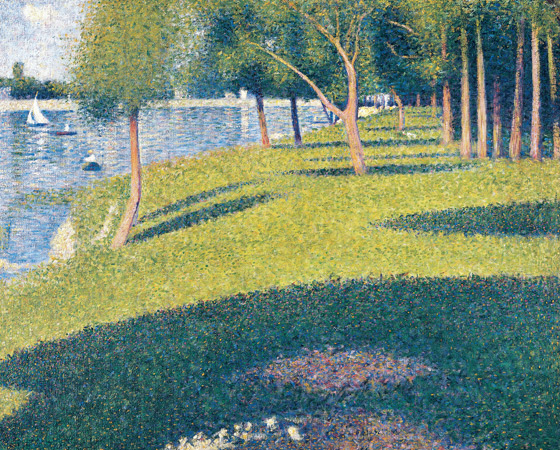

Georges Seurat was a great artist at 25, when he launched his arresting studies for his monumental painting A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte. Six years later, in 1891, he died of diphtheria.

A deeply private man whose friends were surprised to find, at his death, that he had a mistress and two sons, Seurat relied on others to speak for him. The explosive impact of La Grande Jatte, the signature painting of the Art Institute of Chicago, was recognised at once when it was first exhibited in 1886, thanks largely to the sympathetic eye of a brilliant art critic, anarchist, and bomb-making terrorist named Félix Fénéon. The coincidence of a Museum of Modern Art exhibition of Seurat's drawings—"the most beautiful painter's drawings in existence," his close friend Paul Signac called them—and the publication of Luc Sante's vivid translation of Fénéon's fragmentary Novels in Three Lines invites a fresh look at the painter and his spokesman. Rarely do avant-garde art and radical politics cross-pollinate in quite this way.

One of the enduring myths concerning Seurat is that he was a scientist in his use of colored dots.

No one did more to advance this view than Fénéon, a clerk at the War Office who moonlighted (in art historian T. J. Clark's words) as "the best art critic after Baudelaire." Fénéon greeted La Grande Jatte as a "scientific" advance over the merely slap-dash and "improvised" successes of Impressionism, and praised Seurat's cool, impersonal application of paint. "No brag in his brush," he wrote in his own telegraphic prose: "Whether it be on an ostrich plume, a bunch of straw, a wave, or a rock, the handling of the brush remains the same."

Fénéon, who interviewed Seurat at length, borrowed the prestige of modern science in his description of the young artist's methods, which he dubbed "Neo-Impressionism." Ignoring similar effects of juxtaposed color in Delacroix, for example, he claimed that Seurat had drawn on modern color theory to create something altogether new.

Seurat's intermingled dots of green and orange, while "isolated on the canvas, recombine on the retina," according to Fénéon, and "express the scarcely felt action of the sun" on grass. Signac spelled out a shared allegiance to color theory in this psychedelic portrait of Fénéon as top-hatted impresario, offering a make-love-not-war lily to the future.

For Fénéon, scientific rationality underpinned a utopian vision of a perfectly ordered society built on workers' rights, to be achieved, if necessary, by violent means. The subject matter of Seurat's paintings appealed to him as much as the calculated dots of color.

Satire was directed at the "rigid" bourgeois in their Sunday best in La Grande Jatte. In a contrasting painting once owned by Fénéon and now in the National Gallery in London, Seurat portrayed relaxed young workers lounging and bathing across the Seine in the industrial suburb of Asnières. Was Seurat a political radical like his friends Signac, Camille Pissarro ("the anarchist Jew Pissarro," as the anti-Semitic Renoir called him), and Fénéon? Fénéon certainly thought so.

While Seurat kept his opinions to himself, Fénéon noted that "his literary and artistic friends and those who supported his work in the press belonged to anarchist circles; and if Seurat's opinions had differed radically from theirs … the fact would have been noticed."

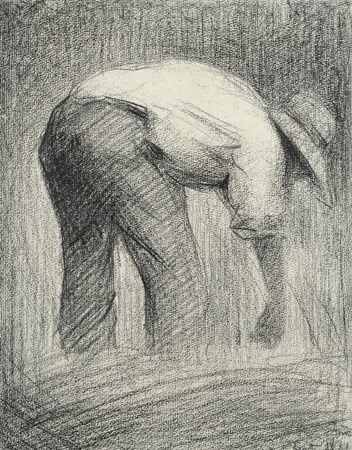

Harvester, 1881. Collection André Bromberg.

Maybe so, but there was nothing revolutionary in Seurat's training as an artist.

Born into a comfortable middle-class family, he studied art and color theory at a municipal school in Paris before entering the conservative Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1878. After leaving the Ecole in 1879 for a year of military service in Brest, Seurat returned to Paris with notebooks—four of which are on view at MoMA—filled with sketches drawn from life. His early drawings look back a generation to Millet in paying tribute to the simple dignity of peasant labor, of which Seurat knew nothing. The real work of a carelessly drawn picture like Harvester, with its safe nostalgia, lies in the way he fills the sheet with the balanced form of the farmer pitched above the hastily scrawled field.

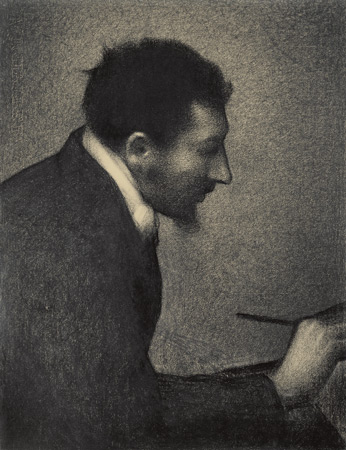

Aman-Jean, c. 1882-83. © 1989 the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Nothing in the Millet-inspired sowers and reapers prepares us for Seurat's beguiling portrait of his studio mate Aman-Jean, with his spiky hair and air of Bohemian intensity. Long recognised as one of the great 19th-century portraits, the drawing is also a velvety tribute to art-making itself. A partially effaced spider web of brushes spans the crook of Aman-Jean's arm, and his tilted, white-knuckled hand has an abstract elegance as it adds a touch to the canvas on the easel. Such drawings make clear that experimentation with color was only a part of Seurat's remarkable achievement, and that his true radicalism lay in his art. Working only with a black conté crayon and sheets of coarse-grained artist's paper, he was already making astonishing drawings in his early 20s.

Influenced by the Symbolist poets and painters he met through Fénéon, Seurat gave a darker, dreamier turn to the favorite subjects of the older Impressionist generation. Instead of the dappled bridges of Monet, we get this jagged rendition of a drawbridge at dusk. The upraised forms of the divided bridge could be two sinister hands playing cat's cradle, with a snarl of string in between. Little in this stunning drawing marks it as dating from the 1880's—it could easily be mistaken for some early sketch of De Kooning or Diebenkorn—except perhaps its brooding intimation of industrial alienation. In contrast to the idyllic harvester, this scene is eerily deserted. And yet there's a restless energy in the violently applied crayon and the swirling sky, and a lingering mystery in the stark composition.

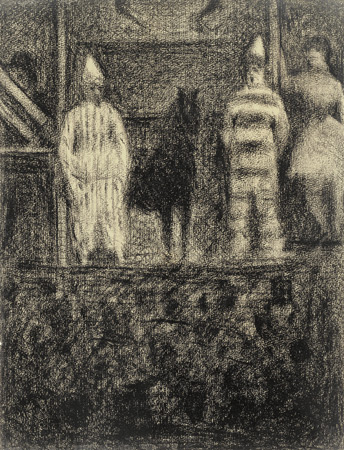

Sidewalk Show, c. 1883–84. The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Urban entertainments in nightclubs and cafes were long familiar, in the work of Degas and Manet, when Seurat began his own tenebrous and melancholy riffs on the subject. This drawing depicts the kind of traveling street show, with pony, clowns, and lady equestrienne, that toured the working-class suburbs and shantytowns on the outskirts of Paris. Seurat found in such spectacles a fusion of urban grit and symbolist dream. The spectators in the lower half of the drawing have morphed into a frieze or barricade of crosshatching. There seems something confrontational in the impersonal audience and the joyless performers in their creepy, Halloween-like costumes.

At the Concert Européen, c. 1886-88. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photograph by John Wronn, Digital Imaging Studio.

During the last years of his life, Seurat's drawings veered toward abstraction—as in these serpentine chair backs and space-alien coiffeurs—and photographic dissolve. Meanwhile, the social tensions implicit in his drawings intensified, in the streets of Paris, amid a wave of violent strikes and bombings. In 1894, Félix Fénéon was arrested by the Parisian police for possession of bomb-making materials, including 11 detonators, and he translated Jane Austen's Northanger Abbey in his jail cell while awaiting trial. (He also remains the prime suspect in the unsolved bombing of the Foyot restaurant that spring.) Cleared of all charges—the jury fell for his charm and his absurd claim that his father had found the explosives in the street—he was fired from the War Office and worked for newspapers instead. For much of 1906, Fénéon filled the columns of Le Matin with brilliant miniature news stories like this: "On the bowling lawn a stroke leveled M. André, 75, of Levallois. While his ball was still rolling he was no more." These fragmented "novels in three lines," according to Luc Sante, enlisted "the detachment and objectivity of science" and "partook of the same essence as the pointillists' adamantine dots." At the time of the trial, Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé told the press that Fénéon's real detonators were his words.

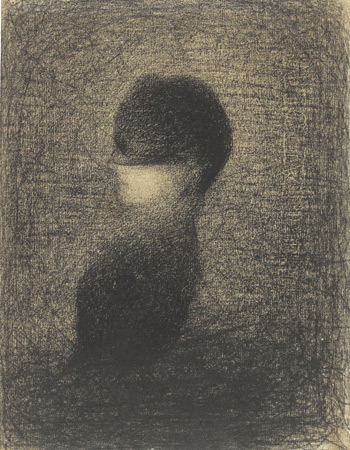

The Veil, c. 1882–84. Musée d'Orsay, Paris. © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource.

Could one say of Seurat that his real detonators were his drawings? If Fénéon was a pointillist in his "novels in three lines," Seurat was a revolutionary in his drawings and paintings. Contributors to the MoMA catalog credit Seurat with, among other achievements, inspiring Van Gogh's broken brush strokes; showing the way toward abstract art; anticipating many of the effects of photography; and predicting the pixels of computers. But always with Seurat, as in the barbed-wire enclosure for this mysteriously veiled cat-woman, there is something that eludes us. As British abstract artist Bridget Riley remarks in a fine tribute in the MoMA catalog, Seurat adopted rational and scientific methods like a "protective shield" and presented us instead with "the mysterious." "Even today I feel a thrill," Riley writes, "when I read Félix Fénéon's first essay on Seurat, which ends: 'Let the hand be numb, but let the eye be agile, perspicacious, cunning.' " Christopher Benfey for Slate

More on pointillists and pointillism:

Hyperpointillism: The Antithesis of Impatience

Randy Glass: Stippling God

No comments:

Post a Comment